|

| Interview in DRUM USA 2008 |

CLICK

TO DOWLOAD WHOLE ARTICLE AS PDF

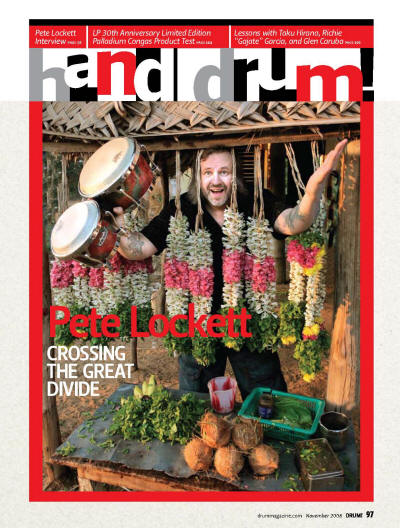

Crossing The Great Divide;

Interview by: Ian Croft

Hybrid styles come easy to the former UK docker whose musical

credentials cover a dazzling array of genres

The all-encompassing view from Pete Lockett’s North London top floor

flat is as cinematic and epic as his musical CV, with the climb up the

curving flights of stairs to his flat bearing testimony to his hectic

scheduling, with the many scuff marks along the walls from numerous

trips up and down with his vast array of percussion instruments

demonstrating the constant demand for his musical expertise.

Lockett’s CV stretches to many, many pages and involves a cross section

of artists that reads like a ‘who’s who’ of popular music.

Whether he is at Ronnie Scott’s with Steve Smith’s Vital Information, or

performing with Shakti’s U Shrinivas, or producing and recording with

Zawinul’s Amit Chatterjee, Pete Lockett is a musical chameleon of

enormous proportions. Peter Gabriel, Robert Plant and Jeff Beck have all

called upon Lockett’s unique percussive ways as has The Verve, Amy

Winehouse and even the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra – and we’re just

scratching the surface here of the broad array of artists expressing a

desire to have Lockett’s percussive imprint grace their work.

Drums and percussion came quite late in life for the former Portsmouth

docker, who at the age of 19 and on his lunch-break took a walk along

the streets of Fratton only to notice an ad in the window of the local

drum store. ‘Drum Lessons’ is all it said. Lockett ventured inside, had

a chat with drum teacher John Hammond and the following week his life

changed – dramatically. “It turned out to the first thing that made

sense to me” says the philosophical Lockett in his quiet friendly tone.

“John was pleasantly surprised too, as everything that he showed to me,

I could do instantly. It was the first time that anything like that had

happened to me. At school, nothing interested me at all, not even music

lessons.”

Since that encounter with Hammond, Lockett has recorded percussion on

the last four Bond movies, currently working on the fifth, performed

around the globe with a dazzling array of musicians and established

himself as one of the ‘first-call’ players in the UK. Lockett has just

released his tuition book on Hudson Music, Indian Rhythms For The

Drumset, a unique approach to playing Indian rhythms – well, on the

drums.

Immersed In Study

Lockett had never shown any interest in music before encountering that

advert and his family household was without music, although “We did have

a radio, but there were no records or musical instruments in the house.

But, as soon as I discovered drum lessons, that was it - big time! Two

weeks later I joined a punk band. I went from a couple of £5 drum

lessons to playing local pubs and clubs overnight.”

Lockett’s first gig was just the start of his unusual musical journey.

“I replaced a drummer who would get tired halfway through a song and

just stop playing. He’d never learnt to use the bass drum pedal and only

ever played with his hands, so it was an easy gig to step into”. Lockett

smiles at the memory. “I used to smash my drums up at the end of every

gig. I even ended up in hospital once to get stitches. I was inspired by

Keith Moon and I loved the drums, the excitement and the energy. It also

taught me a lot about drum building as I couldn’t afford to get mine

repaired and had to rebuild them myself.” Lockett’s diverse instrument

store is testimony to his broad collection of percussive items, some

home made, with many resembling nothing that you would have seen before.

Lockett immersed himself in total study claiming; “At that time

everything stopped for me and I practiced constantly.”

After two years of continual practice, Lockett took the decision to move

to London, despite not knowing a soul there. Times were bleak.

“I rented an old concrete store in Finsbury Park in North London, that

doubled as a bed-sit and the place was just full of dust and was very

cold. It was very depressing.” He recalls with a chill.

In Search of the Music

The London move found Lockett playing kit in Punk and Rock bands. The

Punk era had given way to New Wave and mid 80s London was awash with

bands and gigs. By chance, a friend invited him to his apartment

situated near Alexander Palace, a venue that hosted the Festival of

India where the venue took on the look and sounds of that country. "I

could hear this incredible music and wondered what is that?" The two

took off in search of the music that filtered through the window

following it to its source. "It was a free concert that featured Zakir

Hussain and I'd never seen, or heard anything like it! I was deeply

analytical about drummers and would sit and watch their every move and

watch what they'd do. Even though I couldn't see what they were doing, I

could conceptualize what was going on. One might not be able to do it,

but you could imagine a practice regime that would take you towards

developing that kind of playing. Whereas, with tablas, there is this

massive sound coming out of these tiny little drums and I had no idea

how they were played. Listening to a conga or djembe player, you get an

idea as to what they are doing. With tabla you can't even see what is

happening yet they have this massive sound, this whole tonal spectrum

coming from these small drums. Again, it was this and the lyricism that

attracted me to them.”

Lockett then noticed an advert for tabla lessons and again, that was it!

“Yousuf Ali Khan” was teaching the course and he gave me free lessons

and that was the start of my interest in Indian music. Originally, I

thought that it would compliment my drum-set playing, but I got totally

obsessed by it. I stopped playing in bands and just studied solidly for

six years, firstly with Yousuf and then South Indian music with

“Karakudi Krishnamurthy”.

University of Life

Adamant that he was going to make a career out of music and that he

wasn't going to work a daytime gig Lockett adds "I didn't go to

university, so studying with these great Indian players was my

university”.

Pete also began teaching drums saying; “The first thing that teaching

taught me was that if someone showed me something, it was embedded for

life, but I noticed with some of my students, they'd either forget what

I'd shown them, or they weren't interested. I found this strange, as I

was always so hungry to learn. I realized that not everybody wants to

learn and there are very few people that have the commitment to get it

down - I was shocked.”

Lockett showed one student a straight eighth groove, then the same

groove as a shuffle. “He'd come back and would have learnt the shuffle,

but had forgotten the straight eighth version. In the end I told him

that he might have to think that this wasn't going to work out. I'd save

him from quintuplets!” Lockett chuckles.

Eclectic iPod

By now, Lockett was listening to music across the board and took an

interest in players like Stewart Copeland and Mark Brzezicki, both being

big favorites, as was Steve Gadd. “Chick Corea’s Leprechaun's Dream was

a big influence for me and I'd go and buy a Leo Sayer album just because

it had Gadd on it and you didn't get too many of my friends buy Leo

Sayer albums! I also liked Joni Mitchell and her drummers. I'd listen to

The Who, or Ravi Shankar and to some extent that has reflected in the

player that I am now, as I don't put barriers between things. My iPod is

highly eclectic.”

Back at that time musical education was dramatically different to today.

"Now you can get five-camera angle DVD's, but back then, starting out

playing bongos, I'd never seen anyone play bongos nor could you find a

video that showed you how to do it, so I sat at home and listened to

tracks that featured bongos to try and work out what they were doing and

what was going on. I knew a basic martillo pattern and I was lucky in a

way, as now I have this weird hybrid bongo style due to trying to

discover how it was done.”

Lockett’s study continued. “Even when I first started I always and still

do have this practice routine where I'll have a 30 minute or one hour

session of just playing one thing continually on whatever instrument I'm

working on and every five minutes I move it up by 5bpm. I found that

concentrating upon one thing for that space of time to begin a longer

practice session really brings results.” Continuing, “One problem is

that I'll tour playing tablas for a month and then when I get back I

have a session that requires I play another instrument and I have to

quickly reestablish those techniques on that instrument. But, playing

something really slowly without putting any strain upon yourself for 30

minutes will bring results.” Pete will also cross-fertilize styles,

adding; “Everything has become hybrid and influenced by everything else

so a lot of the techniques have become interspersed onto different

drums, so I might use some of the Indian techniques on the cajon, or

Darabuka.”

A Musical Flow

At a time when the term 'World Music' was in its infancy in the UK it

was not an easy task for Lockett to gain access to the wealth of

material that he so desperately sought.

"I was fascinated with the technique of how it was done and how the

drums produced such an amazing array of sounds.” Lockett concentrated on

learning the many compositional styles and syllables that apply to the

sounds of the strokes and notes making his study all encompassing. “It

was a great way of learning as there was this whole cycle of things that

you go through and memorize. I got deeply into the South Indian musical

culture and learnt the Mridangam and was about to learn the Thavil and

thought, actually, I can either learn that drum or get a career.” And

with that thought Lockett started contacting people, sending them his

CV. Lockett’s first session was for the rock band Thunder. “I got a call

out of the blue to record with them and played tabla, bongos and lots of

various percussion. I went into the studio and it was all rigged out

with skull and cross bones and all other manner of 'rock' trappings, but

as I had long hair, I think I fitted in alright.” he adds. Considering

that this was the late 80s, it was fairly adventurous of Thunder to

consider adding such eclectic instruments as Tablas. "I was shocked as I

got paid decent money to do the things that I really wanted to do!”

The recording experience taught Lockett a valuable lesson. “I always try

and approach everything with an open mind and make everything musical

rather than trying to impress with a dazzling solo. I make music so that

it has some flow to it, rather than a barrage of noise or sounds that

are inappropriate”. Lockett states emphatically.

Organic Beats

The Thunder sessions brought further visibility to Lockett’s adventurous

percussive outings.

“I started to get different things and worked on Bjork's Post record

which was a more Latin flavored session, but I wouldn't call myself a

Latin player, I can play outside of the idiom with that kind of music. I

felt I had put a lot of effort in and I always say that if you send out

a hundred things, expect one phone call, or two at most back. Even with

a big CV it can be two years before you hear anything. Although I mostly

get calls to play percussion my first instrument was the drum set so I

do have to remind people that I can cover that area too”. It’s not just

his inventive playing that Lockett gets called for either. “I'm

currently programming all the percussion for the new Bond movie and I do

what I call organic beat programming, it's not total hardcore

electronics, but there's a lot of electronics and sound design going on.

Craig Armstrong asked me to do the programming for the Incredible Hulk

movie and he's known for a couple of years that I can programme. You

have to be patient. I never hassle people for work because people don't

like being hassled. You make your case, say this is what I can do, you

can listen to it on my site or on the disc that I sent to you and that's

it, leave it to lie and see what comes back.” Lockett genuinely advises.

Cowbell Anyone?

It has ‘happened’ for Pete organically and he has worked hard to get

where he is. “People like to see that your active and I currently have

eight albums out and four more coming out in India this year. Of course

you’ve got to be able to play or no one will call you. You have to get

on with people or the work will quickly dry up. Sometimes, I get asked

for something that I might think might not suit the tabla, but you have

to get to their ideas and I always remain open to what the producer

might be asking for as they obviously want something a little different

that can’t be found on a drum sample CD. I got a call from Roxy Music’s

Phil Manzarena and most of the session was standard stuff and it was

going well and then he wanted me to build a another percussion track on

junk sounds. We took the light down from the ceiling, the bin from the

street came in, the grill from the fire got used and it was great.

Originally, I was thinking that I wasn’t so sure, but it turned out

brilliantly. It opens your mind up for the drums because if you consider

the history of the drum set, there were a lot of percussion instruments

included in the set. Now, it’s just become hardcore drums and a lot of

people wouldn’t even think as far as a cowbell or wood block and how

they could incorporate those sounds.” Lockett states almost

despairingly.

Having an open mind is what has set Lockett on his course of discovery.

“It certainly makes you think how you can use different sounds. Think

about instruments such as congas and bongos, they are commonplace in

popular music now, whereas thirty years ago they were considered exotic

and it’s the same with tabla. Though, that is a harder instrument to

learn, you do hear it incorporated more into popular music.”

Think Musically

It’s not just calls to add some exotic spice to recordings that employs

Lockett’s time. It seems that as fast as he works on one project,

artists involved within that project result in another project being

born.

“Again, that’s something that came to me. I accompanied some artists in

Sardinia for a promoter and it went well and the promoter then advised

on artists for the Rhythm Sticks Festival in London. He asked if I

wanted to play the festival and I genuinely did not know what to say and

said I’d think about it. I had not performed solo before so it was a big

deal at the time. Right before that call I had been working with Joji

Hirota and I thought that we could do a project together that

incorporated Tabla and Taiko drums. I called Joji, we got together and

that was my first sold-out show. The promoter loved it and suddenly we

were doing 30-40 date tours around Europe. Bill Bruford had come to one

of our gigs and I got talking to him and it began the Network of Sparks

project with him.”

It was during these ‘duo’ tours that Lockett had to perform solo spots

that again, made him think musically about what he was doing.

“I know that sitting – respectfully, through a drum clinic, can become a

little boring if people aren’t playing musically. Whether the audience

is all drummers, or simply ‘Bob’ from up the road, you have to give them

something musical to latch onto.”

Tours and sessions continued to introduce musicians to Lockett’s various

projects. “I’ve been working with beat boxer Shlomo and we played the

Glastonbury festival and it was great. There are great talents in all

genres and I try not to pre-conceptualize or be snobbish or judgmental

about different styles and players. It helps keep my ears open to

different influences which helps develop my broader eclectic approach

which in turn makes it difficult to categorize what I do. I like that”

Breaking Down The Barriers

Lockett’s genuine love, respect and dedication for so many different

influences opened many doors for him over recent years, saying;

“Barriers are being broken down and I’ve now found that I am welcomed

and accepted in India at the highest level. In India to collaborate

successfully you do have to know their musical formalities and the

particular ways they work. You are often thrown into gigs without any

rehearsal or sound check and everything is a manic bpm, so that’s the

first thing that you have to get used to and it’s not unusual to play a

two or three hour gig. Even with minimal sound checks, you really need

to think about getting your monitoring correct so that you can hear

everything clearly as they often play on the front edge of the beat.

Technically you have to have real control over what you are doing and

keep it buoyant but without speeding up. It’s like fast be-bop and very

hard to control.”

The Book

I like to give things back. It would be nice if more players did that.

The free lessons on my site are my answer to this. They cover everything

from the basics of bongos to cajon lessons to drum set playing and of

course a lot of the Indian rhythmic systems. The book came about over a

long period of time as I’d been trying to apply the Indian knowledge to

the drum set and it took me many years to do that, to find ways of

articulating those rhythms onto the drum set. Slowly it came about

through other percussion instruments as everything become ‘one’ and

stopped being separate instruments in my mind and I began to think of

them as a family of instruments which is why I call myself a

multi-percussionist. I was teaching the South Indian rhythmic system and

that became the core of the book. Once I had my approach to the system

in place I was able to approach the system in a slightly more abstract

way so that the building blocks could be utilized by all musicians. I

give people the building blocks and would then move on to whole

compositions. I got a lot of positive feedback from students using this

method. They could understand and perceive the building blocks and then

see how they were built into the larger compositions and themes.

The next logical step was to articulate it onto the drums. Really, the

book gives you two things, there is the system that can be for everyone

and then there is the application for the drum set. The book contains

the South Indian syllables / building blocks and the rhythmic structures

and then the applications for anybody to use. I wanted to model the book

on the book that covered African drumming on the drum set where the

first big chunk is the history, the drums, the idiomatic setting and

then the extrapolations on the drum set. I believe it is a book that

will last a long time and is not a moment of fashion that won’t be of

interest in five years. The whole development of the book came from the

education method so it is kind of organic in that way. It never started

out to be a book, but it ended up being one!

www.hudsonmusic.com

RETURN TO INTERVIEWS /

PRESS MAIN PAGE

|