Interview

with: RHYTHM (Summer 98)

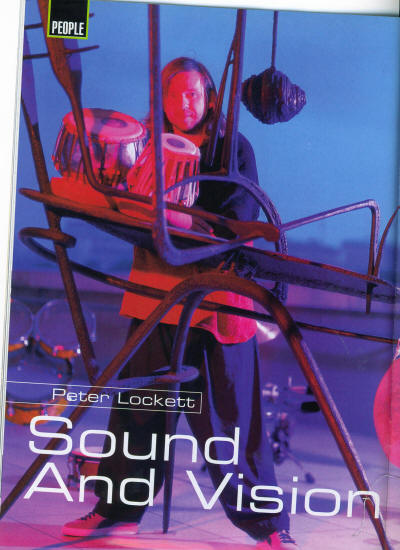

Sound and Vision

Interview:

Mark Walker

He's from Portsmouth. His Hand To Drum series spans five

years of Rhythm history. He's the UK's most unhinged percussionist. You might think you

know all there is to know about Peter Lockett. But you

don't..

To regular Rhythm readers, Peter Lockett is revered as the

man who knows everything that's worth knowing about the percussive side of world music.

For those of you who aren't regular, Pete is a multi-talented drummer and percussionist

whose session credits include Björk, Kula

Shaker, Beth Orton and Transglobal

Underground. Plus, as one of Europe's leading percussionists and tabla players, he

is an integral member of various percussion duos and groups with other world famous

drummers, including Bill Bruford and Joji

Hirota.

He's also an extremely well read chap with enough theories

about music to fill several interviews, using keen illustrations and anecdotes to

demonstrate his points. For example, one of Petes firmest beliefs is that individuality

in music is far more important than getting bogged down with the technicalities of ones

instrument.

Quite often when you learn an instrument you're questioning

yourself, thinking, Well, is it good enough? Or that other people are better than you,

says Pete. I think comparing yourself to other people is very negative and can be very

self damaging. I heard of a guy in Europe, a guitar player, a really good guitar player,

actually, who some months ago tried to kill himself because he thought he wasn't good

enough, which is very deep and very sad. And I'm sure a lot of people feel like that. But

music's not like that, music's about enjoyment and sharing. It's not about barriers,

saying, I'm up on the stage cos I'm fucking good. Bullshit! You're up on the

stage because you're a person in the same room with loads of other people who hopefully

can get something out of the performance together.

Talking to Pete, it soon becomes apparent that the notion of

sharing music and creating music independently, as opposed to conforming to more orthodox

practices, is central to his approach toward his playing. It's important not to adhere to

any tradition too much, he affirms. That's one of the real dangers of learning something

like Indian drumming; that the tradition is so strong it can swamp any creativity that

might be there. There are so many rules and regulations. There's a great quote from

Toffler in Future Shock, which says: The imagination is only free when fear of error

is temporarily laid aside. That's really important, and a lot of people don't

necessarily think about that with their music; they're going on with preconceptions. And

it's not only Indian music that bogs people down with these preconceptions. I think a lot

of people dont know what to do when given a free rein. It's very difficult for people to

choose, and that's why you often get a lot of copycat players in any instrument, because

then it's a known quantity. You go to a gig and you see such and such a player, and people

like it, so you think, People like it, I'll play like that so people will like what I do.

It's natural, it's obvious, but to go out and play with a free pallet is completely

different.

You'll have realised by now that Peter Lockett is a man who

is passionate about music and who puts a lot of thought into what he does. However, many

of his philosophies have come not so much from hours of sleepless nights trying to work

out what it's all about, but from pivotal moments in his career that have turned up out of

the blue. Even his relatively late start in the fine art of drumming, at the age of

nineteen, when he was working as a docker in Portsmouth, was anything but premeditated.

It was a bizarre thing; I was just walking past a drum shop

and I thought, I'll have a drum lesson, for no readily explainable reason, he remembers. I

went in and it made sense to me in a way that other things in my life hadnt before, you

know, education or anything like that. Similarly, his decision to transform himself from

punk rock kit player to tabla guru dude was totally unexpected.

I was playing in a punk band on the London rock scene, and I

accidentally stumbled across an Indian gig. It was Ustad Zakir Hussain

and Ali Akbar Khan, and it was amazing. I didnt know what

they were doing. When you see tabla for the first time, a good player, it's the most

amazing thing, it's stunning. I had no concept of what he was doing, but that made an

impact on me. Later I saw tabla lessons advertised in the local adult education magazine,

and I was down there like a shot. Of course, the actual transformation took somewhat

longer, several years of dedicated study, in fact, although you'd presume it would have

been a fairly enjoyable period of learning.

Yeah, pretty much, but it can be frustrating, Pete explains.

Instruments like the tabla and the mridangam are very different to percussion instruments

like udu, congas or bongos. You can immediately make a sound on those, there's no problem

with that. Of course to articulate with technique is different, but you can make a sound.

With tabla, it's probably eighteen months before you can make a sound at all, it

just sounds terribly pedestrian, the articulation of how you play the drums. And it's very

easy to be dominated by that and just give up. I dont know if I could learn tabla now if I

had to start again. It's the same with the kit drumming; when I first played the kit I

used to stay up all night practising. I can't see myself doing that now. So it's like

blind learning, where you can imagine the end result but you're quite happy that you're

not there yet, and you're just learning by rote. As far as studying goes, at present Pete

is more interested in why he's playing as opposed to how.

The area to master is your philosophy of what you're doing

and why you're doing it, primarily. I want to be able to use what I can do effectively,

and for me, to get more technically able isn't the answer to making music. In fact, if

anything, I want my playing to be dirtier, I want less technique than I've got. And this

dirtier attitude came from another sudden flash of inspiration. One of the turning points

for me was listening to an album by Keith Jarrett called Spirits. He played it all himself, he did everything: tablas,

shakers, piano, guitar, saxophone, flutes, everything. I first got the album because it

had tablas on it; you know, closed mind, Wow, Keith Jarrett playing tablas, I'm going to

get into that! And of course, I got it home, and in my opinion at that time it was rubbish,

so I just gave it away. About eighteen months later someone bought me the same record for

Christmas, and it was incredible - it made such an impact on me, an impact that totally

changed how I see music. If you listen to it, he's playing tablas with mallets and stuff,

but what he's doing is following the contours of the music and making great music on the

tablas with an unorthodox approach. And it made me realise that you can make music on an

instrument without having any technique. Of course you've got to be of a musical mind,

like Keith Jarrett. But it made me think, Well, maybe I'm not on the right path here.

You were too purist perhaps? Not too purist, maybe too...

um... it's a fear. I think developing technically is as much based on fear as it is on

anything else; when I played the drum kit, it was a defence to get technically better, and

I was building a wall around myself which inhibited my playing music with other people. So

I'd get into a musical situation, and my preconceptions of what was good drum-wise might

not fit the music, but I'd say, Well I'm good technically so it doesn't matter, which, of

course, is bollocks. You've got to find whats right for the music. I think a lot

of people use stunning technique as a barrier between them and other people.

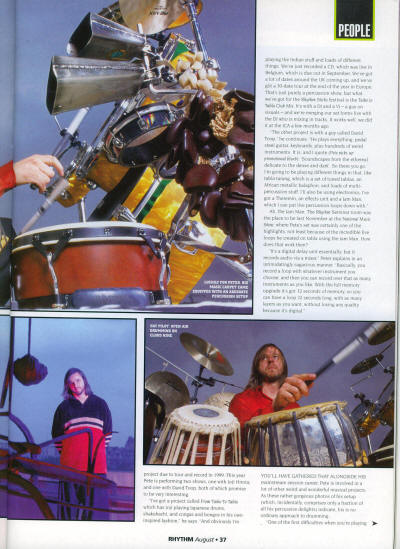

Last year at the South Banks Rhythm

Sticks festival, Pete starred with Bill Bruford in one

of the main headline acts, Network Of Sparks, a project due

to tour and record in 1999. This year Pete is performing two shows, one with Joji Hirota, and one with David Toop,

both of which promise to be very interesting.

I've got a project called From Taiko To

Tabla which has Joji playing Japanese drums, shakuhachi, and congas and bongos in

his own inspired fashion, he says. And obviously I'm playing the Indian stuff and loads of

different things. We've just recorded a CD, which was live in Belgium, which is due out in

September. We've got a lot of dates around the UK coming up, and we've got a 30-date tour

at the end of the year in Europe. That's just purely a percussion show, but what we've got

for the Rhythm Sticks festival is the Taiko to Tabla Club Mix. It's with a DJ and a VJ (a

guy on visuals) and we're merging our set forms live with the DJ who is mixing in tracks.

It works well, we did it at the ICA a few months ago.

The other project is with a guy called David Toop, he

continues. He plays everything: pedal steel guitar, keyboards, plus hundreds of weird

instruments. It is, and I quote (Pete picks up promotional blurb): Soundscapes from the

ethereal delicate to the dense and dark. So there you go. I'm going to be playing

different things in that, like tabla tarang, which is a set of tuned tablas, an African

metallic balaphon, and loads of multi-percussion stuff. I'll also be using electronics;

I've got a Theremin, an effects unit and a Jam Man, which I can put live percussion loops

down with.

Ah, the Jam Man. The Rhythm Seminar room was the

place to be last November at the National Music Show, where

Pete's set was certainly one of the highlights, not least because of the incredible live

loops he created on tabla using the Jam Man. How does that work then? It's a digital delay

unit essentially, but it records audio via a mixer, Peter explains in an intimidatingly

sagacious manner. Basically, you record a loop with whatever instrument you choose, and

then you can record over that as many instruments as you like. With the full memory

upgrade it's got 32 seconds of memory, so you can have a loop 32 seconds long, with as

many layers as you want, without losing any quality because its digital.

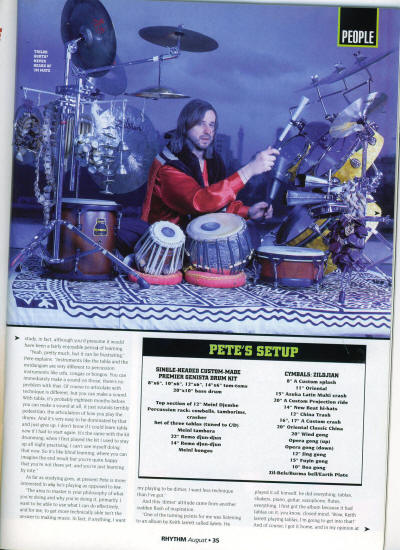

You'll have gathered that alongside his mainstream session

career, Pete is involved in a lot of other weird and wonderful musical projects. As these

rather gorgeous photos of his setup (which, incidentally, comprises only a fraction of all

his percussive delights) indicate, his is no ordinary approach to drumming.

One of the first difficulties when you're playing so many

different things, is choosing a setup, whether you're sitting on the floor, standing up or

sitting on a stool. Most of the time I go for the sitting on the floor option, because

it's the only position you can play tabla properly in, as you're controlling the angle of

the bass drum with your knee for the glissando and the drum moves around a bit. So for a

lot of projects I've built the setup around the floor, with this kit that Premier have

built me on the left, a Meinl tambora, the top of a djembe sawn off, Meinl bongos,

Zildjian cymbals, gongs and Zil-bels, djun-djuns at the back, and lots of different

things. It's good to mix tablas with all sorts of percussion.

Pete designed the Premier kit himself to be played sitting

down, but he's already aware of what some drummers might say when they see it... Well, it

inevitably leads to comparisons with Trilok Gurtu, he sighs, but that's like saying that

all the drummers who sit on stools are copying each other. I think it's a thing that were

going to see more of.

Quite a lot of Pete's work, like his involvement with the

last James Bond movie soundtrack involves special effects, a lot of which he creates

himself with a finely honed combination of technology and a warped mind... If you're going

through an effects unit you can create a lot of interesting tonal delays and pitch

shifting things. You can make a percussive effect out of almost anything that makes a

sound, really. Tie a load of budgerigars together and it would sound amazing! As

would the local RSPB officer battering down the door. As I said at the start, Pete Lockett

has enough philosophies and views about the drummers art to fill several interviews. The

same is true of his tips and advice to those at the beginning of their musical journey. To

finish off, here are a few gems to get you thinking...

There's getting good as a player, or accomplished, shall we

say, and there's becoming a player who's in work; and they're completely different areas.

To get good technically necessitates a little bit of obsession somewhere along the line.

It's difficult because you dont want to be obsessive all your life, but to use the

psychologists parlance, you've got to have some drivers in there to put the work in, to

get it down.

The other important thing is to work out what you want to do.

If you're a family man, if you like being at home, you're probably better off choosing to

go the session route than ending up on a world tour for nine months. I think that's

something you should think about early on; otherwise you can have a disparate angle, and

once you get into one of those areas, work builds up along that line.

So think about whether you want to be a recording player or a

touring player, or whether in fact you want to be writing. Drummers don't always think

about that, and quite often they get a bum deal; they won't be getting writing royalties

and they might not be getting that much money. And if they're a drummer in a band that's

really big for a short while, they then get the disadvantage of being labelled as the drummer

from X, which may not be any good for their future career prospects. So I think it's

important for people to really consider what they want to do.

And the final point, he says in conclusion, is

that you've got to be persistent about it. You've got to carry on, don't give up, don't be

scared of phoning people up and saying, Hello, give me a job, or even, Give me all

your money.

Download PDF version of article

RETURN TO INTERVIEWS /

PRESS MAIN PAGE

|