Pete Lockett looks at the Rhythms of the

Mahgreb and how to clap properly

Most people have quite a vague idea of the specifics of African

drumming. If you were asked what the distinction is between North

African and Central/Southern drumming, what would you answer? Would you

group all African drumming under one umbrella? As we will see from this

article, the drumming of North Africa is very different indeed from the

rest of Africa. The Maghreb is the name given to the five Northern

African states, namely Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia, Mauritania and Libya.

(We’ll look at Egypt a little later.) The word actually means ‘sunset’

in Arabic. The sun sets in the west and therefore, for the Arabic

people, the Northern African mainland is in the west; hence, the Maghreb.

If you look at a map of Africa you will realise that there is one very

important landmark separating these North African countries from the

rest of Africa. The Sahara desert, although the perfect place for

opening up a speculative ice cream shop, is not ideal for travelling

across, camel or not.

For centuries North Africa has been

invaded by many diverse cultures. The influence these invasions has had

on the countries is enormous and is reflected in the shaping of, amongst

other things, the music and percussion. Central and Southern Africa were

not invaded in the same fashion because of the shielding and

uncompromising desert. The Berber people were the native

inhabitants of Maghreb, and the Berber language still survives today.

(For example, one fifth of the population of Algeria speak it while the

majority speak Arabic.) Before looking at the music, it is important to

realise that these countries have experienced rule from cultures as

diverse as French, Roman, Turkish, Arabic and Spanish. Phoenicians and

Carthaginians traded with Berbers but never managed to penetrate inland.

Romans found them unconquerable and gave them the name Berbers. Berbers

called themselves ‘Imazighen’, which means ‘The free men’. It is these

eclectic influences that primarily differentiate Maghreb from Africa.

The northern part of the Maghreb really is far more South Mediterranean

than it is African. Egypt is the one exception in North Africa, being so

close to Jordan, Saudi Arabia and the general Gulf that is

predominantly Middle Eastern and Oriental. The southern part, however,

is far more African. West African influence is very strong,

particularly in the south.

It is often thought that Andalucian music necessarily includes Flamenco.

This overlooks the fact that a form of Andalucian music exists in

Maghreb. In 711 Spain was invaded by Berbers and Arabs who stayed there

until 1492. This period was known as Andalucian Spain. The Arabs of

Spain, with influences from Baghdad, Iraq, formulated the beginnings of

Andalucsan music. During the Fourteenth Century the Andalucian Muslim

and Jewish population were thrown out of Spain and returned to North

Africa. This music then became the classical music of Maghreb, and is

the style of music in which one is most likely to find odd timings. The

construction of the odd timings is not repetitive like in a lot of East

European and Middle Eastern music, but presents itself in the

juxtaposition of odd and even length bars.

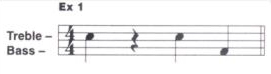

Running alongside this we also get the

folkloric tradition, utilising the more common 4/4, 6/8 and 12/8

timings. Simple as this may sound, it is anything but. The rhythms are

actually extremely difficult because of their elusive off-beat placement

of strategic notes in the bar. The most common misconception is to hear

it backwards or in the wrong place. For example, check ex 1 and 2 for

the basic four and six beat rhythmic frameworks (called chaabi, simply

translating into ‘popular music’ in Arabic). Notice how the bass note is

on beat four in the four beat version. Also notice how the six beat

rhythm resembles the four beat in its general shape. This framework

could be compared to the two basic Afro-Cuban structures of Martillo

(for bongos) and basic Tumbao (as played on the tumba, for example, in

Rumba). The African influence is unmistakable from this comparison

alone.

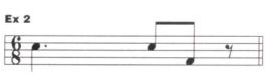

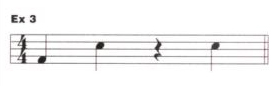

Now look at Examples 3 and 4. (It is what Examples 1 and 2 would look

like if you were hearing them backwards.)

These rhythms are the basic backbone of

a lot of the drumming found in the Maghreb. The patterns are usually

built up by keeping the basic framework and decorating it with ruffs and

ornaments in the gaps (musically, not incessantly). It’s not quite as

simple as that, but one could say that it was a rough synopsis.

The drums of the Maghreb come in many

shapes and sizes, and bear a lot more resemblance to their Middle

Eastern counterparts than they do to their African. We’re going to begin

by looking at a traditional Berber instrument called the bendir. The

bendir is a frame drum made from wood and covered with animal hide. The

qualification for a frame drum is basically any drum in which the shell

is less deep than the head is wide. The wood for these drums is often

bent, usually quite thin. Inside the head of the bendir are a number of

thin strands which stretch across the inside of the head, causing a

vibration not dissimilar to a snare drum when the head is hit. For

maximum effect the head needs to be thin whilst the snares are not too

thin. Drums such as the snared bendir are rarely found anywhere else in

the Middle East because it is a traditional Berber instrument dating

centuries.

The chaabi rhythm is often played on the bendir which, like many Maghreb

percussion instruments, can be played one-handed. It is held with one

hand with the drum head angled downwards, almost facing the floor. The

basic rhythms are articulated by using a full-handed open note and a

full-handed soft slap closed note. It is only rarely that the bendir is

played on the rim, apart from some notes from the hand supporting the

drum.

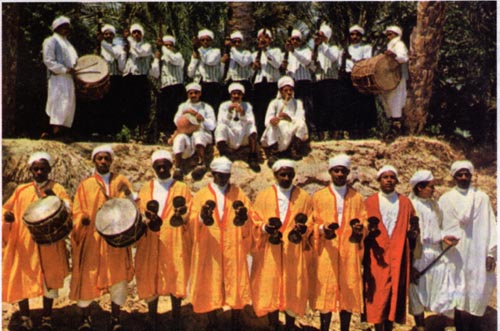

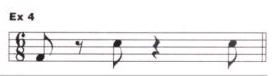

Krakeb, or kakabou (metal castanets), are also essential as building

blocks of the rhythm. Heavy metal beaters shaped like double-ended

spoons are held, two in each hand, and beaten together, usually

contributing a strong semi-quaver level pulse to the groove. The Sufi

group most commonly known for using these are the Gnawa. They go around

to people’s houses on request and play music for them all night, wiith

the intention of healing and trancing them.

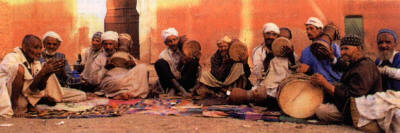

The darabuka is another essential

percussion instrument in the Maghreh. Traditionally made from clay,

goblet shaped and with a fish skin head. The body of the drum is fat at

the top, tapering down into a thinner cylinder for most of the length of

the shell. The drum is sometimes held between the legs but more often is

supported on the thigh and held in place by the forearm in such a way as

to allow the hand to come over the top into a position to strike.

Sometimes the drum is held on the shoulder or between the legs. It is

the first of these three positions which is most common in Maghreb. The

drums are imported from Egypt, especially the new aluminium, tuneable

variety. Anyone who has ever been present at an Algerian or North

African concert will be aware of the enthusiastic audience response of

getting involved and clapping on the beat in very much the same way as

with Qwali music from North India. An authentic clap from this part of

the world is quite astonishing, and not easy to copy. By cupping the

hands into a particular shape and striking in a particular way, you can

hear and feel the air being caught between the two striking hands. The

movement of the arms also appears quite important, being quite relaxed

and flowing. Traditionally it’s common for groups of people to get

together and start clapping. (Similar again to the Spanish tradition)

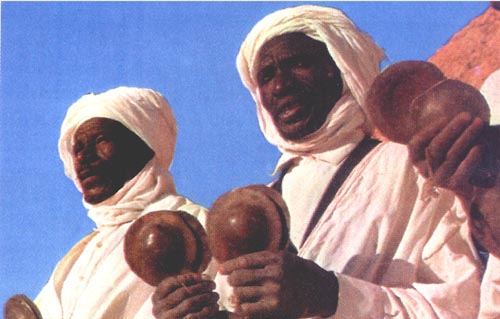

One possible juxtaposition of patterns is given in Example 5 for four

people. It is similar to the Cuban bata drum approach of Santeria, which

we must not forget also has African roots.

This rhythm is also sometimes played on small drums called tarija. The

tarija is a small clay drum shaped like a thin cylinder which splays out

at the top and has a skin at this end. It is held with the left hand,

the skin angled slightly towards the floor. It is hit with the finger of

the other hand. These ensemble drums come in slightly different sizes,

thus giving each drum in the ensemble a different pitch. Another drum

found in Algeria is the guellal, a drum made from a piece of piping with

a skin affixed at one end around the natural bulge of the pipe joint.

(Don’t forget, pipes were around as long ago as the Romans, if not

longer). There is also a snare which is affixed inside this head. This

is the original drum found in Rai music from Algeria. Rai is a youth

music dating back to the 1970s; it comes from a folk music called

wahrani or le genre oranis. Rai was a music which started to address

everyday people’s feelings and emotions through its lyrics. This was a

leap ahead from previous, largely religious lyrics Modern Rai music has

moved on to include instruments such as the drum kit (a multi-pronged,

many headed and peculiar instrument too complex to be encompassed in

this short article) and other standard Western instruments. There is one

important thing to mention about the way the rhythms — as played on the

drum kit — get turned around because of the nature of the traditional

music.

For example, let’s take a basic four beat pattern in ex 6.

Now on the kit, the Africans would play this as the basis of the groove

(ex 7)

We, with our presuppositions, could end up hearing it as this: (ex 8)

With the knowledge of this, some musicians omitted the first snare of

each bar, thus reducing the rhythm to half time but giving it a back

beat whilst retaining the natural feel of the music: (ex 9)

At the end of the day, the music is very

similar in many ways to Qwali music from North India. It is compelling

and draws you into its infectious grooves and melodies. I recommend that

you go and listen to some. Here are a few CDs to get you started:

Cheikha Remitti, LesRacinesDn Rai (Rai Roots 929742 DK 061)

Bellemou Messaoud, Le Pere Du Red (WC DOll)

Khaled, N’SSIN’SSI(519898-2 900)

Houria Aichi, Songs 0/The Aures (Audidis Distribution B6749)

Tabours Du Maroc, Drums 0/Morocco (Aadar Al Sur)

|