|

Scroll down for text and PDF versions.

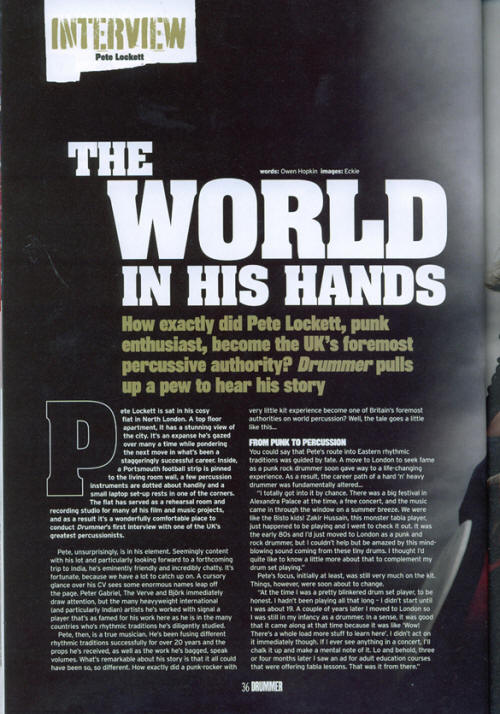

The World In His Hands

Words; Owen Hopkin. Photos; Eckie.

How exactly did Pete Lockett, punk enthusiast, become the UK's

foremost percussive authority? Drummer pulls up a pew to hear his story.

Pete Lockett is sat in his cosy flat in North London. A top floor

apartment, it has a stunning view of the city. It's an expanse he's

gazed over many a time while pondering the next move in what's been a

staggeringly successful career. Inside, a Portsmouth football strip is

pinned to the living room wall, a few percussion instruments are dotted

about handily and a small laptop set-up rests in one of the corners. The

flat has served as a rehearsal room and recording studio for many of his

film and music projects, and as a result it's a wonderfully comfortable

place to conduct Drummer's first interview with one of the UK's greatest

percussionists.

Pete, unsurprisingly, is in his element. Seemingly content with his lot

and particularly looking forward to a forthcoming trip to India, he's

eminently friendly and incredibly chatty. It's fortunate, because we

have a lot to catch up on. A cursory glance over his CV sees some

enormous names leap off the page. Peter Gabriel, The Verve and Bjork

immediately draw attention, but the many heavyweight international (and

particularly Indian) artists he's worked with signal a player that's as

famed for his work here as he is in the many countries' who's rhythmic

traditions he's diligently studied. Pete, then, is a true musician. He's

been fusing different rhythmic traditions successfully for over twenty

years and the props he's received, as well as the work he's bagged,

speak volumes. What's remarkable about his story is that it all could

have been so, so different. How exactly did a punk-rocker with very

little kit experience become one of Britain's foremost authorities on

world percussion? Well, the tale goes a little like this...

You could say that Pete's route into Eastern rhythmic traditions was

guided by fate. A move to London to seek fame as a punk rock drummer

soon gave way to a life-changing experience. As a result, the career

path of a hard'n'heavy drummer was fundamentally altered...

"I totally got into it by chance. There was a big festival in Alexandra

Palace at the time, a free concert, and the music came in through the

window on a summer breeze. We were like the Bisto kids! Zakir Hussein,

this monster Tabla player, just happened to be playing and I went to

check it out. It was the early 80s and I'd just moved to London as a

punk and rock drummer, but I couldn't help but be amazed by this

mind-blowing sound coming from these tiny drums. I thought I'd quite

like to know a little more about that to complement my drum set

playing".

Pete's focus, initially at least, was still very much on the kit.

Things, however, were soon about to change. "At the time I was a pretty

blinkered drum set player, to be honest. I hadn't been playing all that

long -- I didn't start until I was about 19. A couple of years later I

moved to London so I was still in my infancy as a drummer. In a sense,

it was good that it came along at that time because it was like 'Wow!

There's a whole load more stuff to learn here'. I didn't act on it

immediately though. If I ever see anything in a concert, I'll chalk it

up and make a mental note of it. Lo and behold, three or four months

later I saw an ad for adult education courses that were offering Tabla

lessons. That was it from there".

Learning an entirely new rhythmic language clearly wasn't without its

challenges. With the Indian tradition so different to that of the West,

Pete found very little common ground with his new discipline. "Part of

the problem in learning such a complicated system as a Westerner is that

you're not brought up with it. You haven't had the 20-odd years of blind

learning, of seeing people playing it, of knowing a lot about the

instruments' culture and the way the sounds are made. You're really

starting from zero.

"I think 'developed' is the word for the Eastern rhythmic culture rather

than 'complicated'. Technically, it's commonplace in India for everyone

to play to the same level as someone like David Weckl. The postman, say,

plays like Dave Weckl and there are gradients up from there. A lot of

the rhythmic repertoire and techniques that are involved have been

developed over many centuries. It's almost like looking at the Western

drum set in 200 years time -- there'll be such a greater volume of

material to learn that it may also become daunting to someone starting

out. Look at the independence stuff that Thomas Lang's currently

developing or a player like Steve Smith! That could be seen as

intimidating to someone who just wants to learn how to play the kit.

That's a little what it was like learning some of the Indian styles of

percussion. At least a lot of the Western musical repertoire is

accessible!"

Pete, as he'll explain a little later, frequently tours and works in

India, but his percussive schooling was done mainly in the UK. The

reason for this, he says, was purely practical. "A lot of the great

teachers come to the UK anyway and it's probably easier to learn over

here because in India the route is slightly slower and less direct than

Western teaching methods. Obviously, I always learn when I'm out there

-- you can't not learn when you're working with people -- but when I

finally made it out to India I went there as a player so the emphasis

was on gigging".

Unsurprisingly, with the wealth of experience and knowledge he's

gathered, there was plenty to distil and pass on in his new book ĎIndian

Rhythms For The Drum Setí. It sets out to give Western kit players an

insight and a route into Eastern rhythmic traditions and inevitably

highlights the mental shifts required to take on such a task.

"That's right, it looks at the building blocks of the Indian tradition

which, in a sense, is different to what we're used to. We may see a

piece of music as a collection of bars of 3/4, 2/4 etc. Basically

speaking, they would divide that up so that two bars of 4/4 would be

seen as a pattern of 5+5+3+3. Obviously, that can be extended out so you

could have a few bars looking like 5+5+5+3+3+3+5+3 etc. That,

essentially, is how they begin to structure the time flow and the

framework within which they'll shape their phrasing.

ďI really wanted the book to be like a bridge. Yes, the Indian

percussive cultures are developed, but anything thatís developed can be

boiled back down to the building blocks and thatís what Iíve got in the

book Ė the building blocks of rhythm. People can take little chunks of

that and apply it to the drum setĒ. This hybrid spirit has

characterised Peteís career from day one. For him, itís been all about

taking different ideas and working it into his own cultural idiom.

ďAs a musician, itís all about being true to yourself. I don't want to

go off and become an ĎIndian musicianí or a pseudo-Indian. It's about

doing your own thing in that environment and creating new hybrid

soundsĒ. Cross-fertilisation, then, is the name of the game. Itís an

attitude thatís hasnít just paid dividends with the broadening of his

own style, itís also helped him gain a mastery of a staggeringly wide

range of instruments.

ďA lot of the instruments are done to differing degrees. The speciality

stuff is really the hand drumming, Tabla, Darabuka, Bongos and stuff

like that. Some techniques are a lot easier than others to learn. I

donít want to be condescending to any particular instrument, but some

are easier than others. Itís as simple as thatĒ. His musical vocabulary

and skill across a wide range of instruments has seen his CV rack up a

severely impressive list of heavyweight names. Perhaps more impressive

is the name of international artists that feature. Projects like

Taalisman and Repercussion Zone have seen him lock horns musically with

Amit Chatterjee and Bickram Gosh, while Vikky Vinayakram, Selva Ganesh

and Ustad Zakir Hussain also feature.

ďBecause I did all my studying in England, it took a while to finally

get out to India. I think it was 2000 when I did my first tour out

there. To a certain extent, itís a little like it is over here Ė you are

who you play with and you make your name through that. Think of a

musician like Miles Davis and all the incredible players heís brought

through Ė itís a bit like that.

ďThe reaction has been really good when Iíve been out there. I get a lot

of good press, Iíve done a couple of TV specials, so it's going really

well -- I've got 4 albums coming out there this year alone so there's a

lot of stuff happening. I think people are more interested if they see

youíre doing your own projects and albums. They see you in a slightly

different way rather than just a session guy who just turns up. They see

someone whoís trying to create and put together tours as a positive

thing, which is how it should beĒ.

The many rhythmic traditions heís experienced and techniques heís

studied has re-enforced one common message. Knowledge is one thing, says

Pete, but it doesnít count for much if it isnít used musically.

ďWhatever genre or cultural idiom youíve got there are people who play

musically and people who donít. You could have a Tabla player who isnít

musical at all and could be all over it like a rash making it sound

really horrible. I think knowledge of different traditions is essential,

but it has to be used musically Ė thatís what we do at the end of the

dayĒ

Click for low res PDF of article

Click for HI res PDF of article

|